Impulse Function, Signal Classes and Fourier Properties

Posted by Anonymous and classified in Design and Engineering

Written on in  English with a size of 23.38 KB

English with a size of 23.38 KB

Properties of the Impulse Function

Answer

The impulse function, often denoted as the Dirac delta function δ(t), has several important properties that make it a useful tool in mathematics, physics, and engineering, particularly in signal processing and systems analysis. Here are the key properties:

Sifting Property

The most important property of the Dirac delta function is its sifting property. For any continuous function f(t):

∫−∞∞ f(t) δ(t − t0) dt = f(t0)

This means the integral of a function multiplied by the delta function picks out the value of the function at t0.

Normalization

The integral of the delta function over the entire real line equals one:

∫−∞∞ δ(t) dt = 1

Scaling Property

If a is a nonzero constant, then the delta function scales as:

δ(a t) = (1 / |a|) δ(t)

Shifting Property

The delta function can be shifted in time: δ(t − t0) represents an impulse occurring at time t0.

Derivative of the Delta Function

The derivative of the delta function, δʼ(t), satisfies:

∫−∞∞ f(t) δʼ(t − t0) dt = −fʼ(t0)

Convolution with the Delta Function

Convolving a function f(t) with the delta function yields the function itself:

f(t) * δ(t) = f(t)

Classification of Signals

Answer

Signals can be classified based on various criteria including their time domain behavior, amplitude, periodicity, symmetry, energy/power, determinism, and application. Common classifications include:

1. Based on Time Characteristics

- Continuous-time signals: Defined for all time (e.g., analog sine waves).

- Discrete-time signals: Defined only at discrete time instants (e.g., sampled signals).

2. Based on Amplitude Characteristics

- Analog signals: Can take any value in a range (continuous amplitude).

- Digital signals: Take a finite set of values (e.g., binary values 0 and 1).

3. Based on Periodicity

- Periodic signals: Repeat at regular intervals (e.g., sine waves).

- Aperiodic signals: Do not repeat (e.g., noise, transient signals).

4. Based on Symmetry

- Even signals: Symmetric about t = 0 (e.g., cosine).

- Odd signals: Anti-symmetric about t = 0 (e.g., sine).

5. Based on Energy and Power

- Energy signals: Finite energy E = ∫−∞∞ |x(t)|² dt (0 < E < ∞). Examples: pulses, decaying exponentials.

- Power signals: Finite average power but infinite energy. Power P = limT→∞ (1 / 2T) ∫−TT |x(t)|² dt (0 < P < ∞). Examples: sinusoids.

6. Based on Determinism

- Deterministic signals: Exactly described by a mathematical expression (e.g., sinusoids).

- Random signals: Characterized statistically (e.g., noise).

7. Based on Applications

- Communication signals: For information transmission (audio, video).

- Control signals: Used to regulate systems.

- Sensor signals: Generated by sensors (temperature, pressure).

Periodic and Aperiodic Signals

Answer

Periodic and aperiodic signals are key in signal processing and communications:

Periodic Signal

A signal x(t) is periodic if there exists a fundamental period T such that:

x(t) = x(t + T) for all t.

Examples: sine wave, square wave. Characteristics: definite period T, repetitive, representable by Fourier Series.

Aperiodic Signal

An aperiodic signal does not repeat at fixed intervals and has no fundamental period. Examples: exponentially decaying signals, speech, noise. Typically analyzed with the Fourier Transform rather than Fourier Series.

Key difference: Periodic signals exhibit cyclic behavior; aperiodic do not.

Complex Exponential

Answer

A complex exponential has the form:

x(t) = A e^{j(ω t + φ)}

where A is amplitude, j is the imaginary unit, ω is angular frequency, and φ is phase.

Key Properties

- Euler's formula: e^{jθ} = cos(θ) + j sin(θ).

- Oscillatory behavior: Represents sinusoidal oscillations.

- Real and imaginary parts: A e^{jωt} = A cos(ωt) + j A sin(ωt).

- Fourier analysis: Complex exponentials form the basis for Fourier Series and Transforms.

- Multiplicative property: e^{j a} ⋅ e^{j b} = e^{j(a + b)}.

- Period: Repeats every 2π / ω.

Energy and Power Signals

Answer

Signals are classified by their energy and power:

Energy Signal

Signal x(t) is an energy signal if its energy E = ∫−∞∞ |x(t)|² dt is finite (0 < E < ∞). Typical examples: pulses, decaying exponentials.

Power Signal

Signal x(t) is a power signal if it has finite nonzero average power but infinite energy. Power is computed as:

P = limT→∞ (1 / 2T) ∫−TT |x(t)|² dt

Examples: sinusoidal signals, ongoing random processes.

Key differences

Energy: finite vs infinite. Power: zero vs finite. Energy signals are often transients; power signals model persistent oscillatory behavior.

Bounded and Unbounded Signals

Answer

Signals are bounded if their amplitude remains within a finite value M for all time:

|x(t)| ≤ M for all t (M finite).

Unbounded signals grow without bound as t → ∞ (e.g., exponential growth, ramp functions). Bounded signals are preferred in control and engineering to ensure stability.

Discrete-Time Signal and Its Representation

Answer

Discrete-time signals are defined only at discrete instants and are denoted x[n], where n is an integer. Representation methods include:

- Graphical representation

- Functional representation

- Tabular representation

- Sequence representation

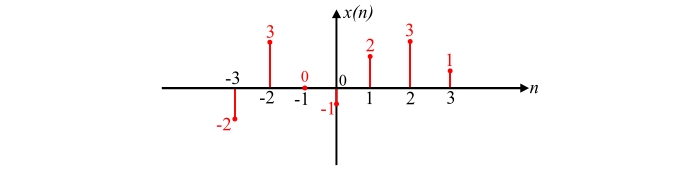

Graphical Representation of Discrete-Time Signals

Consider the discrete-time signal x[n] with values:

x[−3] = −2, x[−2] = 3, x[−1] = 0, x[0] = −1, x[1] = 2, x[2] = 3, x[3] = 1

This discrete-time signal can be represented graphically (see figure below):

Functional Representation of Discrete-Time Signal

Writing magnitude against n gives:

x[n] = { −2 for n = −3; 3 for n = −2; 0 for n = −1; −1 for n = 0; 2 for n = 1; 3 for n = 2; 1 for n = 3 }

Tabular Representation of Discrete-Time Signal

Sample index n and the corresponding x[n] value in table form:

| n | −3 | −2 | −1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| x[n] | −2 | 3 | 0 | −1 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

Sequence Representation of Discrete-Time Signal

The sequence representation lists the samples; the arrow denotes n = 0:

x[n] = { −2, 3, 0, −1, 2, 3, 1 ↑ }

When no arrow is shown, the first term corresponds to n = 0 by convention.

Sum and Products of Discrete-Time Sequences

Sum: The sum of two sequences is element-wise: if c[n] = a[n] + b[n], then c[n] = a[n] + b[n].

Product: The product of two sequences is element-wise: c[n] = a[n] · b[n].

Scalar multiplication: The product of a sequence and a constant k yields c[n] = k · a[n].

Tabular Representation of Discrete-Time Signal: (duplicate content retained as required)

| n | −3 | −2 | −1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| x[n] | −2 | 3 | 0 | −1 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

Operations on Discrete-Time Signals (DTS)

Answer

Operations on discrete-time signals include mathematical manipulations useful for analysis and processing.

1. Basic Operations

- Addition: y[n] = x1[n] + x2[n]

- Subtraction: y[n] = x1[n] − x2[n]

- Multiplication (element-wise): y[n] = x1[n] · x2[n]

2. Time Shifting

- Advance (right shift): y[n] = x[n − k]

- Delay (left shift): y[n] = x[n + k]

3. Scaling

- Amplitude scaling: y[n] = A x[n]

- Time scaling: y[n] = x[k n]

4. Folding (Time Reversal)

Reflect the signal across n = 0: y[n] = x[−n]

5. Convolution

Fundamental operation for linear systems:

y[n] = Σk=−∞∞ x1[k] · x2[n − k]

Used for system analysis, filtering, and digital communications.

6. Differencing (First Difference)

Numerical differentiation: y[n] = x[n] − x[n − 1]

7. Accumulation (Summation)

Discrete integration over time: y[n] = Σk=−∞n x[k]

Relationship Between Impulse and Step Function

Answer

The impulse (delta) and step functions are closely related via differentiation and integration.

1. Impulse Function (Dirac Delta)

- The impulse δ(t) is zero everywhere except at t = 0 and integrates to one: ∫−∞∞ δ(t) dt = 1.

- It models a sudden instantaneous change.

2. Step Function (Unit Step)

The unit step u(t) is defined as:

u(t) = { 1, t ≥ 0; 0, t < 0 }

It represents a signal that switches ON at t = 0.

3. Relationship

Differentiation

The derivative of the unit step yields the delta:

d/dt u(t) = δ(t)

Integration

The integral of the delta yields the unit step:

∫−∞t δ(τ) dτ = u(t)

4. Physical Interpretation

- The impulse models an instantaneous force or change.

- The step models a cumulative effect (switching from OFF to ON).

Properties of the Delta Function (Summary)

Answer

Key properties already noted include:

1. Sifting Property

∫−∞∞ f(t) δ(t − a) dt = f(a)

2. Integral Property

∫−∞∞ δ(t) dt = 1

3. Time Scaling

δ(a t) = (1 / |a|) δ(t)

4. Time Shifting

δ(t − a) represents an impulse at t = a.

5. Differentiation

d/dt u(t) = δ(t)

6. Fourier Transform

The Fourier transform of δ(t) is a constant in frequency (contains all frequencies equally): F{δ(t)} = 1

Static and Dynamic Systems

Answer

Static System

A static (memoryless) system's output depends only on the current input. Characteristics: no memory, instantaneous response. Examples: algebraic relations like V = IR.

Dynamic System

A dynamic system has memory; the output depends on current and past inputs and evolves over time. Often described by differential or difference equations. Examples: circuits with capacitors/inductors, mechanical systems with inertia.

Key Differences

| Property | Static System | Dynamic System |

|---|---|---|

| Memory | No memory | Has memory |

| Response | Instantaneous | Evolves over time |

| Equation Type | Algebraic | Differential or difference |

Causal, Non-Causal and Anti-Causal Systems

Answer

Classification by causality:

- Causal system: Output at time t depends only on present and past inputs. (Real-time physical systems are typically causal.)

- Non-causal system: Output depends on future inputs as well as past/present. Used in offline processing or theoretical analyses.

- Anti-causal system: Output depends only on future inputs (not physically real-time implementable).

Time-Invariant and Time-Variant Systems

Time-invariant systems preserve the shape of responses under time shifts. Time-variant systems have properties that change with time (e.g., varying gain).

| Feature | Time-Invariant | Time-Variant |

|---|---|---|

| Response Shift | Maintains shift | Changes with time |

| Equation Stability | Remains same | Varies over time |

Linear and Nonlinear Systems

Answer

Linear systems obey superposition and scaling. Nonlinear systems do not.

Linear System

- Superposition: x1 → y1 and x2 → y2 implies x1 + x2 → y1 + y2.

- Scaling: k x(t) → k y(t).

- Characteristics: predictable, analyzable by linear methods.

Nonlinear System

- Does not satisfy superposition or scaling. Can exhibit complex behaviors such as chaos and bifurcations.

- Often requires numerical methods for analysis.

Key Differences

| Property | Linear System | Nonlinear System |

|---|---|---|

| Superposition | Holds | Does not hold |

| Scaling | Holds | Does not hold |

| Complexity | Simple | Complex, possibly chaotic |

Stable and Unstable Systems

Answer

System stability describes whether bounded inputs produce bounded outputs (BIBO stability).

Stable System

If |x(t)| is bounded, then |y(t)| is bounded. Stable systems' responses settle and remain predictable.

Unstable System

A bounded input can produce an unbounded output (|y(t)| → ∞). This requires stabilization techniques.

Marginally Stable

System that neither grows unbounded nor decays; it oscillates indefinitely (e.g., ideal undamped LC circuit).

Key Differences

| Property | Stable | Unstable | Marginally Stable |

|---|---|---|---|

| Output Growth | Bounded | Unbounded | Neither decays nor grows |

Invertible and Non-Invertible Systems

Answer

An invertible system allows recovery of the input uniquely from the output; a non-invertible system loses information.

Invertible System

There exists an inverse system H−1 such that H−1[y(t)] = x(t). Example: multiplication by a nonzero constant.

Non-Invertible System

No unique inverse exists; information loss occurs (e.g., squaring function y = x²).

Continuous-Time Fourier Series (CTFS)

Answer

CTFS decomposes a periodic signal into complex exponentials:

x(t) = Σn=−∞∞ Cn e^{j n ω0 t}

where ω0 = 2π / T and the Fourier coefficients are:

Cn = (1 / T) ∫0T x(t) e^{−j n ω0 t} dt

Alternate Sinusoidal Form

x(t) = A0 + Σn=1∞ [An cos(n ω0 t) + Bn sin(n ω0 t)]

Properties and Applications

- Periodicity, orthogonality, convergence conditions.

- Used in signal analysis, audio and image processing, circuit frequency response.

Properties of Fourier Series

Answer

- Linearity: Fourier coefficients add for sum of signals.

- Periodicity: Applies only to periodic signals.

- Symmetry: Even signals contain only cosines; odd signals only sines.

- Time shifting: Shifts introduce phase factors to coefficients.

- Frequency shifting, convolution, differentiation/integration, Parseval's theorem, Gibbs phenomenon.

Properties of Fourier Transform

Answer

The Fourier Transform converts time-domain signals into frequency-domain representations. Key properties include:

- Linearity

- Time shifting: x(t − t0) ⇒ X(f) e^{−j 2π f t0}

- Frequency shifting

- Convolution: Time-domain convolution ⇒ frequency-domain multiplication.

- Differentiation in time ⇔ multiplication by j 2π f in frequency.

- Parseval's theorem: energy equality between time and frequency domains.

- Time scaling and duality.

- Inverse Fourier Transform: x(t) = ∫−∞∞ X(f) e^{j 2π f t} df

Properties of the DTFT

Answer

The Discrete-Time Fourier Transform (DTFT) analyzes discrete signals in frequency domain. Key properties:

- Linearity

- Time shifting: x[n − n0] ⇒ e^{−j ω n0} X(ω)

- Frequency shifting

- Convolution: Time-domain convolution ⇒ frequency-domain multiplication.

- Parseval's theorem: Σn |x[n]|² = (1 / 2π) ∫−ππ |X(ω)|² dω

- Periodicity: DTFT is 2π-periodic: X(ω) = X(ω + 2π).

- Duality: symmetry between time and frequency representations.

Key Causality Differences (Summary Table)

| Type | Depends on Past | Depends on Present | Depends on Future |

|---|---|---|---|

| Causal | Yes | Yes | No |

| Non-Causal | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Anti-Causal | No | No | Yes |

Causality is a crucial concept in control systems, signal processing, and physics.